Insights from a Classroom Conversation on Defining Mediation

A definition can be a doorway or a dead end. When we ask students training to become mediators to choose the definition of mediation they most align with, we’re not just testing their understanding of theory. We’re inviting them to reflect on the values, roles, and responsibilities they believe should shape mediation practice. And the answers they give can be surprisingly revealing.

In a recent postgraduate university mediation class, students were asked to review a range of professional definitions of mediation from national standards to academic textbooks and explain which one they preferred and why. The responses were thoughtful, often passionate, and collectively painted a picture of a new generation of mediators stepping into the field with strong ethical instincts and a desire for clarity and structure.

Which Definitions Did They Prefer?

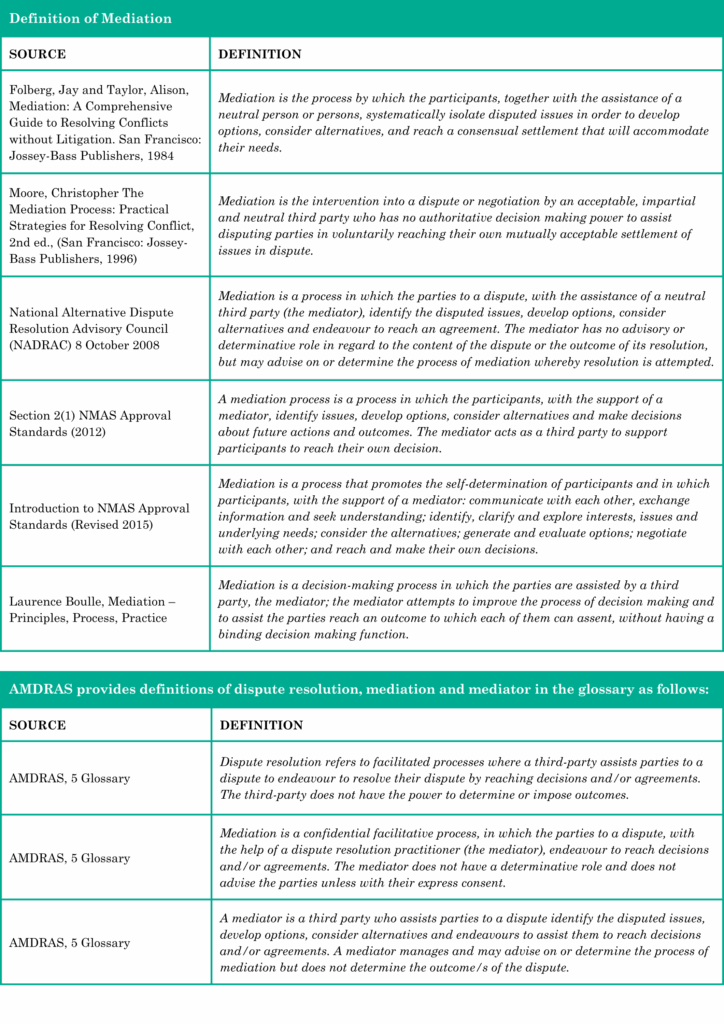

The students had several formal definitions to choose from, including:

-

The NMAS Approval Standards (2015 Revised)

-

The National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (NADRAC)

-

Laurence Boulle’s textbook definition

-

The classic description by Folberg and Taylor

-

Christopher Moore’s influential framework

-

The more recent AMDRAS (Australian Mediation and Dispute Resolution Accreditation Standards) definition

-

A few chose or offered more generic, simplified definitions.

Out of 40 students, their preferences fell roughly as follows:

-

18 students chose the NMAS (2015 Revised) definition

-

6 students preferred NADRAC’s

-

5 students aligned with Laurence Boulle

-

3 students chose Folberg and Taylor

-

3 students cited the AMDRAS definition

-

1 student preferred Christopher Moore’s

-

4 students gave their own simplified definition or did not specify a formal source

Why NMAS (2015) Was the Clear Favourite

What made the NMAS 2015 definition so compelling for students?

Its strength lies in its structure and specificity. Unlike other definitions that outline the spirit or purpose of mediation in broad strokes, NMAS provides a step-by-step map of the process from communication and understanding, through exploring interests and options, to decision-making. It’s both practical and values-driven.

Students consistently praised its:

Emphasis on party self-determination

Many students were drawn to the way this definition placed the power firmly in the hands of the parties. Several explicitly contrasted this with court or arbitration processes.

Clarity of mediator role

The definition carefully outlines the mediator’s function as a process supporter not a decision-maker, advisor, or evaluator something students saw as ethically important.

Detail and transparency

The list-style format (communication, interest identification, option generation, negotiation, decision-making) made the process feel real and understandable, especially for those new to mediation.

As one student put it:

“Mediation is not just about reaching agreement it’s about creating constructive dialogue and restoring relationships when possible.”

Another student likened it to a family meeting:

“It lets everyone speak, instead of parents just giving orders.”

This metaphor reflects the students’ intuitive grasp of mediation’s democratic, relational nature and their sensitivity to power dynamics.

What About the Other Definitions?

Although NMAS dominated, other definitions still found support and for interesting reasons.

NADRAC’s Definition

This was valued for its balance of structure and flexibility. Students appreciated that it allowed for professional process design while preserving party autonomy.

“Effective mediation requires skilled process management without compromising party self-determination.”

Some saw this as a better fit for complex or high-conflict disputes where a more active mediator might be needed to keep things on track.

Laurence Boulle’s definition

Boulle’s definition was praised for its clarity and neutrality. Students liked that it was concise, captured the essentials, and didn’t tie mediation to any one model (e.g., purely facilitative). For some, it offered a good “middle ground.”

“Definition should be concise. This one captures the essence: parties making decisions, assisted by a mediator.”

Folberg and Taylor

This definition attracted students who were looking for a more relational or needs-based lens. Its emphasis on mutual understanding and accommodating interests resonated with students who saw mediation as a way to address underlying human needs, not just disputes.

AMDRAS

A few students specifically chose the AMDRAS definition because of its professional and formal tone. They valued its alignment with contemporary Australian standards and its clarity on confidentiality and ethical boundaries.

Emerging themes

Regardless of which definition they chose, a few consistent values echoed through nearly every student response:

1. Party Autonomy Matters Deeply

Students repeatedly underscored that mediation should empower the parties not the mediator. This wasn’t just lip service; many cited real or observed cases where they felt power was misused or parties were sidelined.

2. Mediator as Facilitator, Not Fixer

Most students were cautious about the mediator stepping into directive roles. Even those who supported NADRAC’s more active framing were careful to emphasize that the mediator should not be determinative.

3. Clarity Helps Learning (and Practice)

Several students noted that clearer definitions helped them understand what actually happens in mediation. Definitions that laid out steps and roles in practical terms felt more useful, especially for those beginning to build a practice framework.

“This definition explains what mediation is and how it works. That’s important for learning and for doing it properly.”

4. Theory Meets Ethics

Some students explicitly questioned where power lies in mediation. A few raised concerns about what’s left out of formal definitions such as how to deal with power imbalances, cultural difference, or emotional intensity.

One student cited Haavi Morreim’s emphasis on ethical vigilance:

“Mediators or lawyers making decisions for the parties without authorisation… erode the right to self-determination.”

This attention to ethics, often unprompted, was a striking and encouraging theme.

Why This Matters

At first glance, this might seem like a simple classroom exercise. But asking students to choose and defend a definition of mediation turns out to be a powerful reflective tool. It requires them to wrestle with:

What values they think mediation should uphold

How the mediator’s role should be shaped and bounded

What kind of process they want to facilitate or experience

It’s also an early step in developing their professional identity. Their choices suggest a generation of mediators who are keen to uphold party autonomy, resist easy answers, and think critically about the work they’re training to do.

And for those of us guiding them, their reflections are a reminder to keep our own definitions alive, dynamic, and under constant thoughtful revision.

Questions for reflection

Definitions and Values

How do you define mediation?

What values are embedded in your preferred definition (e.g., autonomy, collaboration, efficiency, justice)?

Does your definition lean more toward describing what mediation is or what it should achieve? Why?

Are there values or concepts you feel are often missing from formal definitions? (e.g., cultural responsiveness, power awareness, trauma sensitivity?)

The Mediator’s Role

Do you see yourself primarily as a facilitator, a guide, or something else?

How comfortable are you with the idea of being more directive or evaluative in certain situations?

How does your preferred definition influence the way you manage power dynamics in the room?

Professional Identity

What does your working definition of mediation reveal about your approach to practice?

How might your definition shape how clients see you—and what they expect of the process?

Has your understanding of mediation changed over time? If so, what shaped that shift?

Context and Change

Do you think definitions of mediation need to evolve to address contemporary issues (e.g., cultural difference, neurodiversity, AI in mediation)?

How might different definitions of mediation influence how the field develops in the future?