By Dr Samantha Hardy

Inspired by Jennifer L. Schulz (2023). Mediator Liability 23 Years Later: The “Three C’s” of Case Law, Codes, & Custom. Ottawa Law Review / Revue de droit d’Ottawa, 55(1):151–186. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7202/1112508ar

A Quiet Assumption

For many of us working in the mediation field, there’s a quiet assumption we rarely question: that we’re not likely to be sued for what happens in a mediation room.

And, to date, that assumption has mostly held true. While a few attempts to sue mediators have occurred in different jurisdictions around the world, none have resulted in a mediator having to pay compensation to a party.

Canadian mediator and law professor Jennifer Schulz reviews 23 years of case law across six common law countries—including Australia—asking why mediators are not being held liable and arguing that they should be. The article is well worth reading in full, as the detailed summaries of the cases examined provide a vivid picture of the current gap between our aspirational standards of practice and the lack of accountability for those who do not meet them.

The Current Reality: A Legal Shield

Schulz’s research confirms what many of us might suspect: across Canada, the US, Australia, New Zealand, England, and South Africa, courts are still not holding mediators legally liable for negligent practice.

Even in cases involving mediator coercion, numerical errors in settlements, inappropriate behaviour, or poor handling of vulnerable parties, the most common judicial response is to set aside the agreement—not to hold the mediator accountable.

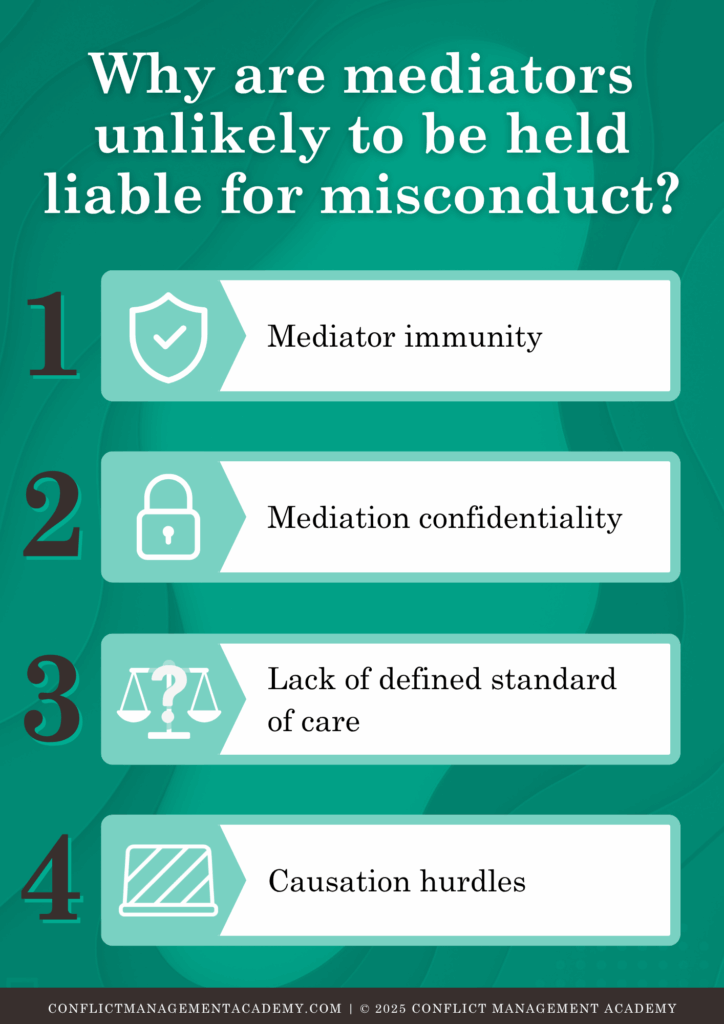

There are four main reasons for this legal shield:

Mediator immunity – either through legislation (as in many US states and Australian courts) or through contractual terms.

Mediation confidentiality – which often prevents complainants from even introducing evidence of wrongdoing.

Lack of a defined standard of care – without it, there’s nothing to measure negligence against.

Causation hurdles – it’s hard to prove that a mediator’s actions caused a party’s loss.

As Schulz puts it, we’re operating in a legal vacuum—where professional expectations are high, but legal consequences are rare.

The “Three C’s” Proposal: A Way Forward?

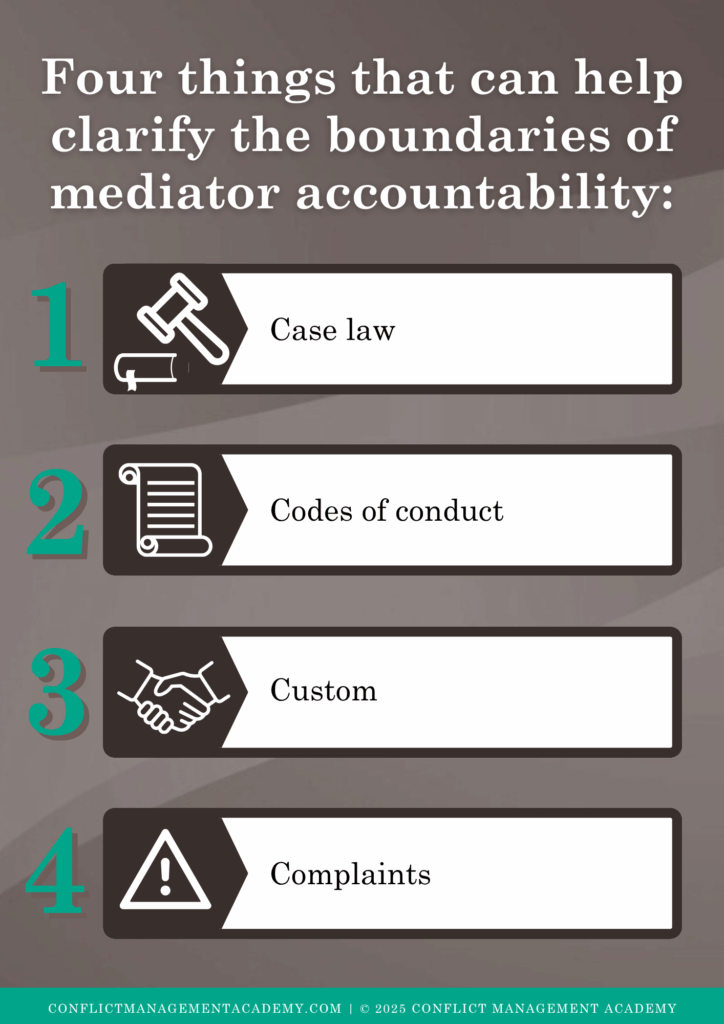

Schulz doesn’t advocate for a wave of mediator lawsuits. Instead, she proposes a more thoughtful framework for developing legal accountability: the Three C’s.

Case Law – court decisions that, even if inconsistent, begin to sketch the boundaries of acceptable practice.

Codes of Conduct – such as those issued by AMDRAS, state-based mediator panels, or court-connected schemes.

Custom – what a reasonable mediator would do in a given situation, based on community norms and practice standards.

I would personally add another C, perhaps attached to the Codes of Conduct item – and that is Complaints. More could be done to educate clients about what they should be able to expect from their mediator, and mediator complaints services could be more courageous and transparent about how they respond to client complaints. Complaints handling that is half-hearted or that aims to protect mediators rather than hold them publicly accountable only exacerbates the problem and pushes it underground.

These sources could help courts (and the profession) articulate what counts as competent mediation (the basis for a standard of care in negligence) and what crosses the line.

What the Cases Tell Us

The article walks through dozens of cases—some troubling, some absurd, many familiar. A few key themes emerge:

1. Coercive Behaviour Is Common—But Unpunished

Multiple cases involve mediators who pressured parties to settle, made legal predictions, lost their tempers, or belittled participants. Courts have rarely responded with consequences—unless the party was unrepresented and severely disadvantaged. The courts typically assume that if a party is legally represented, their lawyer will protect them from any harm.

Notably, some cases even include allegations of racist or discriminatory remarks by mediators—again, without findings of liability.

2. Vulnerability Is Often Overlooked

Incapacity cases—where a party was overwhelmed, unwell, or otherwise unable to engage effectively—are nearly always dismissed. Courts seem to assume that the voluntary nature of mediation allows a party to stop participating at any time, so choosing to continue negates their right to claim. This type of thinking shows a lack of understanding of how incapacity might show up, in that it might also make someone incapable of making a good choice to leave the mediation.

3. Mediators Who Make Mistakes Still Escape Consequence

From drafting errors to bad legal advice, mediators are largely shielded unless the consequences are glaring and the party can prove they were misled into harm. In such cases, courts tend to place responsibility on the parties’ lawyers—even where the mediator dictated the settlement. Even where there is no lawyer involved, the likely outcome is that the agreement will be set aside, rather than any consequences for the mediator.

Implications for Australian Practice

So what does this mean for those of us practising under the AMDRAS framework or in private, court-connected, or hybrid contexts?

Legal immunity doesn’t mean ethical impunity. Just because we’re unlikely to be sued doesn’t mean we shouldn’t hold ourselves—and each other—to higher standards.

Custom matters. If the law ever does change, it will likely rely on what we say is normal, ethical, and good practice in our mediation communities.

The codes we sign up to should guide us daily—not just when we’re audited or accredited. They may form the basis of future legal standards.

Training matters. When mediators pressure parties, overlook incapacity, or provide questionable advice, it’s often due to poor training, not bad intentions.

RABs need to have rigorous complaints processes. Until the courts step up and impose consequences on mediators who behave badly, the mediator’s accreditation body must be able to manage complaints effectively to prevent harm to parties and the profession’s reputation. This means holding mediators accountable for improper behaviour and educating members about where the line will be drawn.

Industry/peak bodies could play an important role in educating clients about their rights/expectations of a mediator. It’s one thing for mediators to hold themselves accountable (and be required to do so through professional standards). It’s another for a client to be informed and educated about the treatment they are entitled to receive.

It is also important to acknowledge that there are many cases in which aggrieved clients lash out at mediators who have done nothing wrong. Vexatious complaints seem particularly common in the family sector, and it is important that the practitioners involved are treated with respect and allowed to defend themselves with dignity.

A Profession at the Crossroads

Mediation has come a long way—from fringe alternative to mainstream dispute resolution. With that growth comes a challenge: do we want the status of a profession without the accountability?

Schulz’s article offers a roadmap. The future of mediator liability may not lie in sudden lawsuits or rigid standards, but in a profession willing to evolve its own definitions of excellence, to recognise when harm has been done, and to hold people accountable.

As Australian mediators, particularly with the new AMDRAS standards about to come into effect, we’re well placed to lead this conversation. The question is: will we?